The experimental band Can were formed in Cologne in 1968. Keyboardist Irmin Schmidt and bassist Holger Czukay came from avant-garde classical backgrounds, studying with Stockhausen. Schmidt’s mind was opened to the artistic possibilities of rock music on a trip to New York in 1966, while Czukay was impressed by The Beatles‘ ‘I Am The Walrus’, and became a fan of The Velvet Underground and Frank Zappa. The core of the band was completed with free-jazz drummer Jaki Liebezeit and guitarist Michael Karoli. Karoli was a 19-year-old student of Czukay, while the other German members of Can were already in their thirties.

Introduction

Can recruited American sculptor Malcolm Mooney as lead vocalist. Mooney featured on the band’s early work before quitting for mental health reasons in late 1969. He was replaced by Japanese vocalist Damo Suzuki, whom the group encountered busking outside a Munich cafe. Suzuki was the lead vocalist for the band’s best-known works in the early 1970s.

Suzuki left Can after 1973’s Future Days to become a Jehovah’s Witness. The band soldiered on, using existing members for lead vocals, before petering out in 1979. The original lineup reformed with Mooney for 1989’s Rite Time.

Can were a diverse collective of musicians, who each added something unique to Can. Czukay’s skills as an engineer shaped Can’s improvisations into coherent albums, while Liebezeit was an awe-inspiring drummer with his metronome precision; his hypnotic grooves with Czukay make the band accessible. Karoli’s acid-rock guitar adds muscle, while Suzuki’s vocals are cryptic and charismatic.

Many of Can’s songs are based on the modal approach, where the group would improvise around a single chord. Can’s improvisational approach was groundbreaking and influential, and they’re an important touchstone for a lot of subsequent experimental rock and electronic music. Radiohead cited Can as an influence on their shift away from rock music on 2000’s Kid A and covered ‘The Thief’ live. Johnny Rotten, Mark E. Smith, Mark Hollis, Stephen Malkmus, Thurston Moore, and Bobby Gillespie have all acknowledged Can’s influence. Multiple bands have also taken their names from Can tracks, including Spoon and Hunters & Collectors.

Can Album Reviews

Delay 1968

1981, 6.5/10

Can’s first recording sessions weren’t accepted by a label, and they weren’t released until 1981. They capture Can at their most primitive – the sound quality is rough, and there’s a garage band feel to songs like ‘Nineteenth Century Man’. The album was originally titled Prepared to Meet Thy PNOOM, and would have included ‘Father Cannot Yell’ and ‘Outside My Door’, both of which were used on the subsequent Monster Movie. Malcolm Mooney has charisma, but his vocal ability is limited, and his straightforward bluster can become wearying on longer tracks.

Most indicative of Can’s future direction is the drum and bass groove that propels ‘The Thief’. It’s topped off by a surprisingly strong Mooney vocal, where he uses a higher register than usual, bringing out his appealing rasp. The harsher sounds of ‘Uphill’ are furthest away from the psychedelia of much of Delay 1968. The two longer tracks that bookend the record are less enticing, but the closing ‘Little Star of Bethlehem’ has its moments of compelling groove and fun guitar freakouts from Karoli.

It wasn’t released until 1981, but Delay would have made for a stronger debut album than Monster Movie, especially if it had included ‘Father Cannot Yell’ and ‘Outside My Door’.

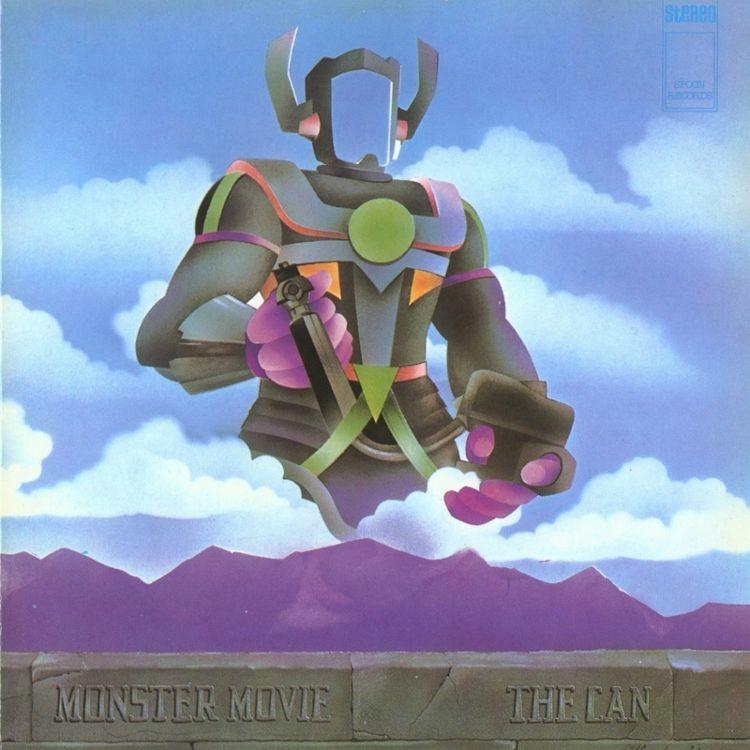

Monster Movie

1969, 6/10

Can’s first album is credited to “The Can” – the group had recently changed their name from Inner Space. It’s their only studio album with Malcolm Mooney, apart from 1989’s reunion on Rite Time. Recorded at Schloss Nörvenich, a 14th-century castle, Monster Movie is a step forward from Delay 1968 in terms of sound quality, but it’s less consistent, especially as the entire second side is dedicated to the overlong ‘Yoo Doo Right’.

Frighteningly, ‘Yoo Doo Right’ was edited down from six hours of tapes – it would have worked as a short song, but it drags at twenty minutes, lacking the spacey, expansive sound of Can’s best work. The first side of Monster Movie is much more interesting – the opener ‘Father Cannot Yell’ anticipates post-punk, ten years ahead of the curve, while ‘Mary, Mary So Contrary’ sounds like a template for early Roxy Music.

There are a lot of groundbreaking ideas on Monster Movie, but dedicating an entire second side to ‘Yoo Doo Right’ doesn’t make for a great album.

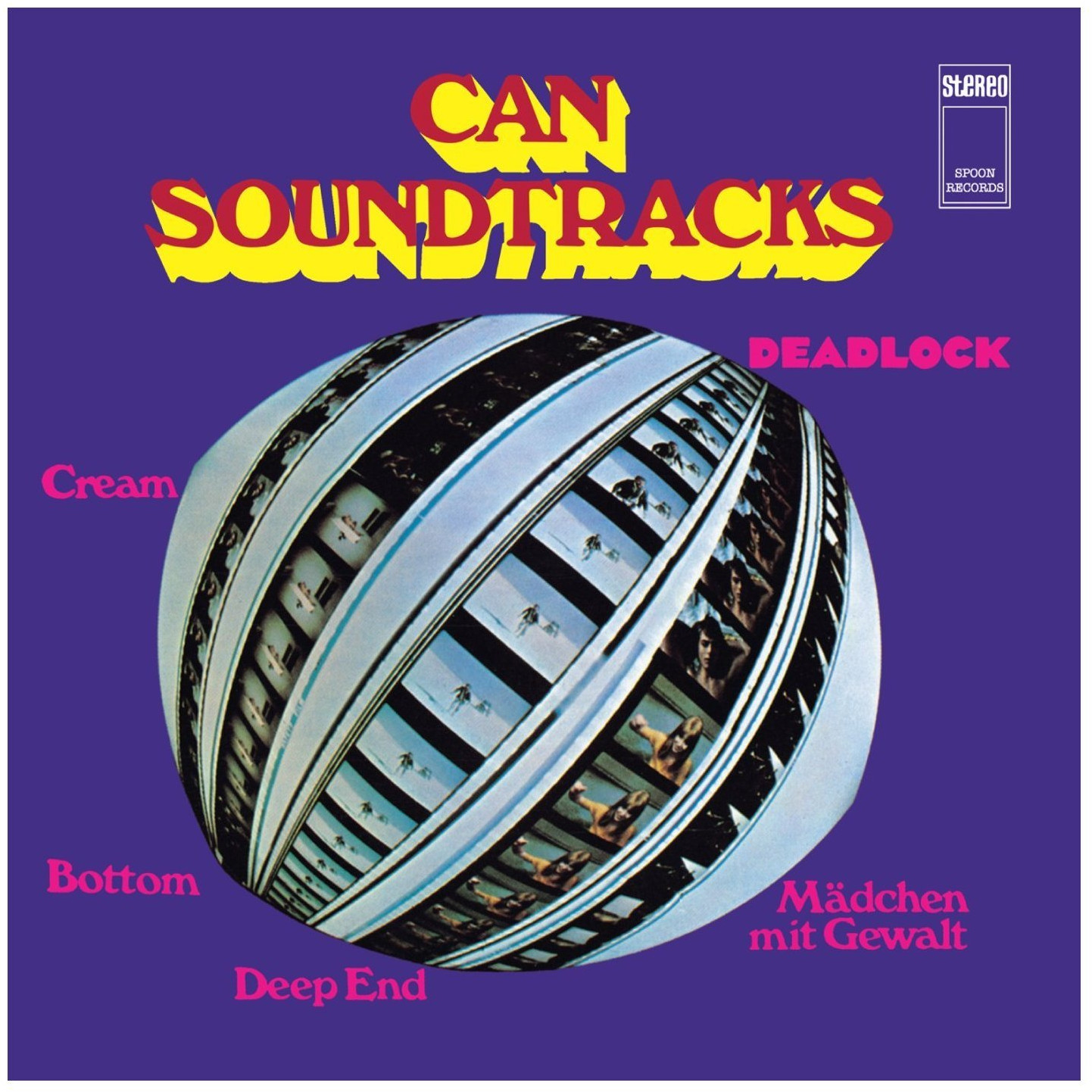

Soundtracks

1970, 8/10

Like Pink Floyd in the same era, Can made music for art-house movies. Soundtracks is a collection of these songs, and it showcases the transformation of the group during a pivotal stage in their development. ‘She Brings The Rain’ and ‘Soul Desert’ feature Malcolm Mooney on lead vocals, while new vocalist Damo Suzuki is featured on the other five tracks.

The change in vocalists is coupled with a change in musical approach. The tracks with Suzuki are more spacey and futuristic. While Mooney’s vocals were distinctive and schizophrenic, Suzuki’s less conventional – his lyrics are often undecipherable and he’s more like another instrument.

The epic track here is ‘Mother Sky’, a fifteen-minute tour de force that’s among Can’s best songs. Karoli’s guitar squalls and Suzuki’s lyrics vie for attention. Opinions on the internet about what Suzuki’s singing vary, but I prefer the interpretation “I say madness is too pure like mother sky.” Mooney’s ‘She Brings The Rain’ is unusual territory for Can, almost heading into swinging Sinatra.

Soundtracks is a compilation rather than a studio album, but it features some of Can’s best work. Along with their next three albums, it’s part of Can’s most artistically rich phase.

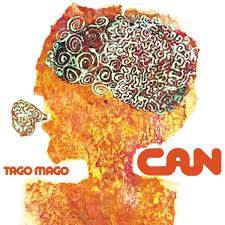

Tago Mago

1971, 9/10

Can originally envisaged Tago Mago, their first full album with Damo Suzuki, as a single album. Their manager, Hildegard Schmidt (married to Irmin), convinced them to make a double album, with the second LP showcasing their more esoteric material. Tago Mago was recorded in the Schloss Nörvenich, a 15th-century castle, courtesy of wealthy art Herr Vohwinkel.

Tago Mago is often regarded as Can’s seminal album, and it showcases the group’s different strengths. There’s an LP side of relatively accessible and succinct songs, a side dedicated to the monster groove of ‘Halleluhwah’, and the sidelong ‘Aumgn’, with Can at their most free-form.

The first three songs are a great place to start an exploration into Can – the foreboding ‘Mushroom’ is book-ended by ‘Paperhouse’ and ‘Oh Yeah’, upbeat tunes driven by Leibezeit’s beats and Karoli’s acid guitar. ‘Halleluwah’ is often singled out as Can’s signature song, and it’s based around a monstrous drum groove from Leibezeit, creating a foundation for the other members to improvise around. Suzuki references the first side’s track names during the ‘Hallehluwah’ lyrics, reciting “mushroom head, oh yeah, paper house.”

Schmidt uses sine-wave generators and oscillators on ‘Aumgn’, instead of his usual keyboards. It makes for a tough listen – it’s an atmospheric soundscape that largely forgoes usual Western music structures. Can never took themselves too seriously, and ‘Augmn’ is followed by ‘Peking O’, with Czukay’s tape experiments to the fore.

Seventeen minutes of ‘Augmn’ is challenging, but overall Tago Mago is an amazingly creative, vibrant album that often sounds decades ahead of its time.

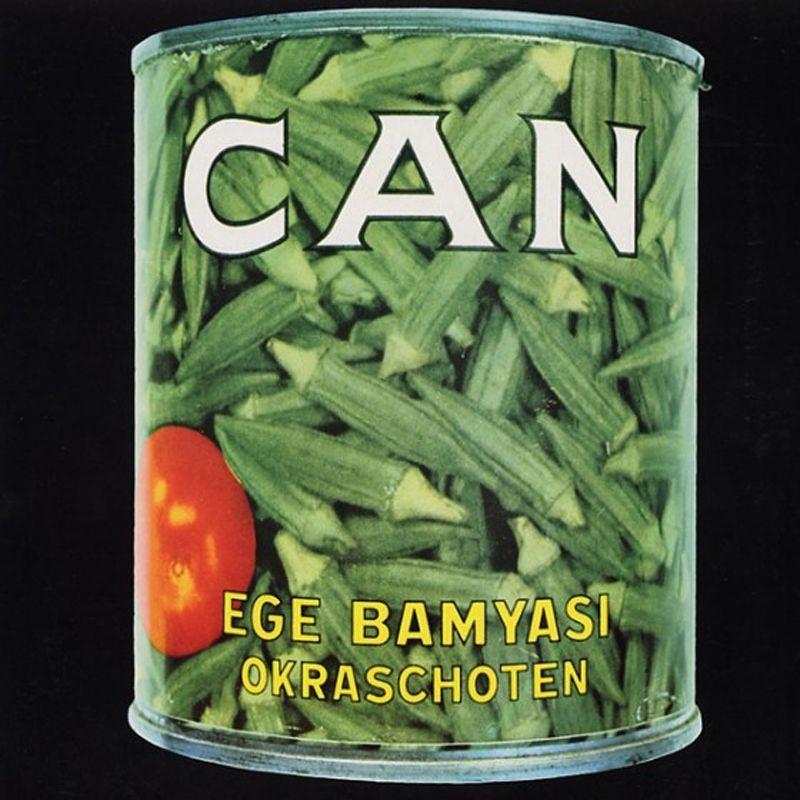

Ege Bamyasi

1972, 8.5/10

The title of Can’s fourth studio album is Turkish for Aegean okra. Ege Bamyasi contains an unlikely hit single – its final track ‘Spoon’ was released before the album, and it hit #6 in Germany after its inclusion in the mini-series Das Messer. The success of the single allowed Can to hire an ex-cinema near Cologne to use as a recording and living space, but the creation of Ege Bamyasi was interrupted by Schmidt and Suzuki’s obsessive chess playing. Like the first LP side of Tago Mago, Ege Bamyasi features relatively succinct songs (by art-rock standards) flavoured with psychedelia and funk;

Ege Bamyasi lacks a central epic like Can’s other Suzuki albums, but there are plenty of minor pleasures. ‘Pinch’ is another rhythmic driving song like ‘Halleluwah’, while ‘Soup’ starts intensely before unwinding into an entertaining sound collage. There’s also the gentle ‘Sing Swan Song’, the stuttering ‘One More Night’, and while ‘Spoon’ doesn’t sound like a hit single, it’s tuneful and succinct.

Ege Bamyasi doesn’t break much new ground for Can, but it’s the most accessible record from the Damo Suzuki era.

Future Days

1973, 9.5/10

Ege Bamyasi was largely groove-focused, built around Leibezeit’s driving rhythms. Future Days dials the intensity right back, with Schmidt’s synth washes taking the central role, and Leibezeit playing gentle jazz parts. The term ambient hadn’t yet been coined in 1973, but Future Days is certainly heading in that direction, slowly unfolding over long tracks. Future Days was Suzuki’s last album with Can; he later stated that it was “the best album I made with Can… I wanted nothing from them after that.”

The outlier among the four tracks is ‘Moonshake’ – it’s a succinct and upbeat piece that would have fitted on Ege Bamyasi. But the three lengthy tracks dominate the tone of the record – they’re gentle and calm. The title track features Suzuki singing about “Saving money for a rainy day / For the sake of future days,” over a percolating rhythm. ‘Bel Air’ is a suite of four different tracks stitched together.

It’s a completely different record than Tago Mago, but Future Days is another peak for Can, full of languid beauty.

Soon Over Babaluma

1974, 6.5/10

Damo Suzuki left Can in early 1974 to marry a Jehovah’s Witness, and wasn’t replaced. Instead, Karoli and Schmidt took over vocal duties, although neither had the charisma of Suzuki. As a result, Soon Over Babaluma loses the primal rawness of rock music, and the clinical precision of jazz is at the forefront. Some of Soon Over Babaluma continues the ambient sounds of Future Days, especially the closing ‘Quantum Physics’, but overall it’s more energetic.

Karoli’s violin playing is featured more heavily than before, starting from the strong opener ‘Dizzy Dizzy’. Karoli’s low-key vocals are more effective than Schmidt’s kooky efforts on ‘Come Sta, La Luna’. ‘Chain Reaction’ is the disc’s most abrasive song – Can still sound far ahead of their time on the more abrasive sections, especially Leibezeit’s bed of percussion.

Can are a different proposition without Suzuki. Soon Over Babaluma is a worthy effort with plenty of interesting ideas, but it suffers without a charismatic focal point.

Landed

1975, 6/10

Can’s second post-Suzuki album found the group bolstered by a major technical upgrade – the two-track recorder they’d used at Inner Space was replaced by a sixteen-track machine. It mostly serves to further detract from the group’s identity – while previously, they’d worked most of their pieces out of jams, now they could record and overdub like a normal studio band.

Landed shares the same sterile, jazzy feel as Soon Over Babaluma, although it is more rhythmically diverse – ‘Half Past One’ inches towards reggae, while the opening ‘Full Moon on the Highway’ is surprisingly close to generic 1970s hard rock. Saxophonist Olaf Kübler of Amon Düül guests on ‘Red Hot Indians’, while the lengthy closer ‘Unfinished’ is closest to the group’s previous exploratory jams.

It’s fun to hear Karoli and Leibezeit show their chops, but Can are less enthralling without a specialist vocalist.

Unlimited Edition

1976, 5.5/10

Can released the compilation Limited Edition in 1974 – as the title implies, it was limited to 15,000 copies. An expanded version was issued in 1976, with a second disc that adds seven more tracks. As a sweep-up of out-takes, it caters for the Can obsessive, taking in tracks from all of the band’s eras thus far.

Perhaps surprisingly, the 1960s Mooney material is the most engaging. ‘Fall of Another Year’ is pretty, with Leibezeit playing clarinet (I think? I can’t tell wind instruments apart….). ‘Mother Upduff’ takes some cues from The Velvet Underground’s ‘The Gift’, but Mooney’s charismatic delivery shines on the macabre tale of grandmother and octopus. For Suzuki, there’s a nice Ege Bamyasi out-take ‘I’m Too Leise’, and ‘Doko E’ from the Future Days era. The instrumental material is less enticing – there’s eighteen minutes of ‘Cutaway’, and a series of short Ethnological Forgery Series tracks where Can imitate different genres of world music.

Unlimited Edition is worth wading through for the highlights, but it’s essentially an appendix for dedicated fans.

Can 1976-1991

Can soldiered on for four more studio albums:

– Flow Motion (1976)

– Saw Delight (1977)

– Out of Reach (1978)

– Can (1979)

Flow Motion featured the disco-flavoured hit ‘I Want More’. Can added ex-Traffic members Rosko Gee and Rebop Kwaku Baah to the lineup starting with Saw Delight, with Gee taking over bass duties and Czukay switching to experimental effects. The group broke up after 1979’s Can, but reformed (the original lineup, with Czukay and Malcolm Mooney) for 1989’s Rite Time. Based on the two tracks featured on Anthology, it’s an embarrassing finale for a once-great band.

Anthology

1994, not rated

Can are a tough band to anthologise. Their best material is concentrated heavily in the Damo Suzuki era, and their best songs are lengthy. There are weird decisions, nevertheless – including the full twenty-minute version of ‘Yoo Doo Right’, and a mere five-minute edit of ‘Halleluwah’ is bizarre. Not naming the compilation Canthology is also a missed trick. If I was making a two-disc compilation, I’d opt for one disc covering their lengthy epics from the Suzuki era (‘Mother Sky’, ‘Halleluwah’, ‘Soup’, ‘Bel Air’, ‘Future Days’), and a chronological overview of shorter songs on the other disc.

I included Anthology on this reviews page as it was my only Can album for a long time, but you’re better off listening to their best albums individually.

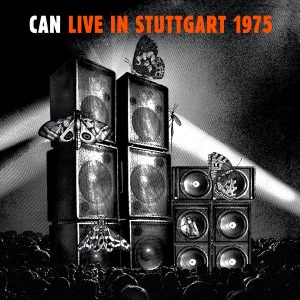

Live in Stuttgart 1975

2021, 8/10

When Damo Suzuki left German avant-garde band Can after 1973’s Future Days, they didn’t replace their shamanistic front-man. Instead, guitarist Michael Karoli and keyboardist Irmin Schmidt took over on lead vocals, and the band’s studio work lost a lot of its appeal. But Live in Stuttgart shows that the post-Suzuki version of the band remained a formidable live act. Their studio albums from the period feel too smooth and sanitised, but live their personalities as players shine through. Drummer Jaki Liebezeit was one of the most formidable players of the rock era, with the steadiness of a drum machine, while bassist Holger Czukay’s grooves are crucial to the band’s live sound.

At this point in their career, the band didn’t play a setlist. All these tracks are improvised as the surviving member of this quartet, Irmin Schmidt, explained to Flood.

The key, because we risked going on stage, always, without knowing what we were going to play. We came on stage and reacted to the atmosphere of the room, of the crowd, the ambience of the scene, and the lights. Of course, to each other. All spontaneously together. That, of course, is a risk, because…if you don’t have a set of songs, you invent.

The lengthy jams of Live in Stuttgart aren’t necessarily something I’ll return to often, but Can in full-flight are impressive regardless.

Ten Best Can Songs

Halleluwah

Mother Sky

Future Days

The Thief

Bel Air

Oh Yeah

Soup

Father Cannot Yell

Spoon

Paperhouse

Back to 1970s Album Reviews….

Related Pages

About

Aphoristic Album Reviews is almost entirely written by one person. It features album reviews and blog posts across a growing spectrum of popular music.

Review Pages

Read about the discographies of musical acts from the 1960s to the present day. Browse this site's review archives or enjoy these random selections:

Blog Posts

I add new blog posts to this website every week. Browse the archives or enjoy these random selections: